LibUV Thread Pool: Deep Dive

Welcome back! It’s time to look at libuv’s thread pool. This is the piece that handles “blocking” OS-style work (like crypto and filesystem) away from the single JavaScript thread so your API stays responsive.

Libuv is full of secrets, and this investigation won’t be easy. There are many things we don’t know yet. So, what are we waiting for? Let’s head to the police station and question Libuv until we find the answers. It’s time to close this case for Season 1!

We’ve already talked a lot about Libuv, but there are still a few questions we need answers to. Specifically, we haven't looked at the idle, prepare, and pending callback phases These are important, and today, we’re going to clear them up.

Ready, detectives? Let’s dive in and solve these mysteries. You can also check the official NodeJs documentation here: https://nodejs.org/en/learn/asynchronous-work/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick

Pending callback

As we know, all file and connection-related tasks are handled in the poll phase, right? But sometimes, there’s a possibility of a process getting stuck in the poll phase. This could happen for various reasons, like recursive calls, errors, or a large number of requests, which may cause delays. To avoid such situations, if there are any pending callbacks, they get executed in the pending callback phase.

This phase is not super important in everyday work, but academically, you should be aware of it. If you have the time, go ahead and read more about it. Essentially, it executes I/O callbacks that were deferred to the next iteration of the event loop.

idle/prepare

In this phase, checks take place within the event loop, and it is performed internally. As I mentioned earlier, this phase is more for academic understanding. If you're interested, go ahead and read the official NodeJs documentation on the event loop. Keep in mind that the official docs might have different diagrams or images, but don’t get confused. Just focus on understanding the concept. You can also read more about libuv design here.

The poll phase is the most important phase of the event loop, and idle/prepare takes place right before it.

Homework: Can you find out where in the code the event loop waits at the poll phase if there's nothing to run?

What is a Tick?

In NodeJs, one complete cycle of the event loop is called a tick.

Logic of Waiting in Poll Phase

Before the event loop enters the poll phase, it calculates how long it needs to wait there. The logic behind this is not too complex, but it can be tricky to explain without going into code examples. It’s best to explore this topic by reading the actual code and checking out blogs or videos available online. Best of luck with that!

Sorry, explaining this in writing can be tough, but in the future, when you're relaxing in a garden, I’ll think of a simpler way to explain this. Stay tuned! For now, just remember that the event loop is the master in libuv.

Mystery of Thread Pool

We know that libuv handles different types of tasks, like DNS, cryptography, file access, OS-related tasks, and timers. These are complex tasks that are processed by libuv. For example, when libuv receives a file read request, it uses one of its threads from the thread pool to handle it. The request comes during the poll phase, and libuv sends it to the thread pool. The thread then transfers the file access to the OS and becomes available for new tasks. The same process happens for cryptography and other tasks.

What is a Thread?

A thread is like a container that runs code. If you want to block it to perform some work, you can do that. Remember, this thread is different from the main thread. When we talk about the main thread, we are referring to the V8 engine's main thread, which runs plain JavaScript. On the other hand, the threads we are discussing here are part of the thread pool in libuv.

Libuv uses multiple threads. For example, if one file system request comes in, it will use one thread, and if another request comes in, it will use another thread. Requests keep coming, and these threads handle them by blocking and processing them as needed.

Size of thread pool (UV thread pool)

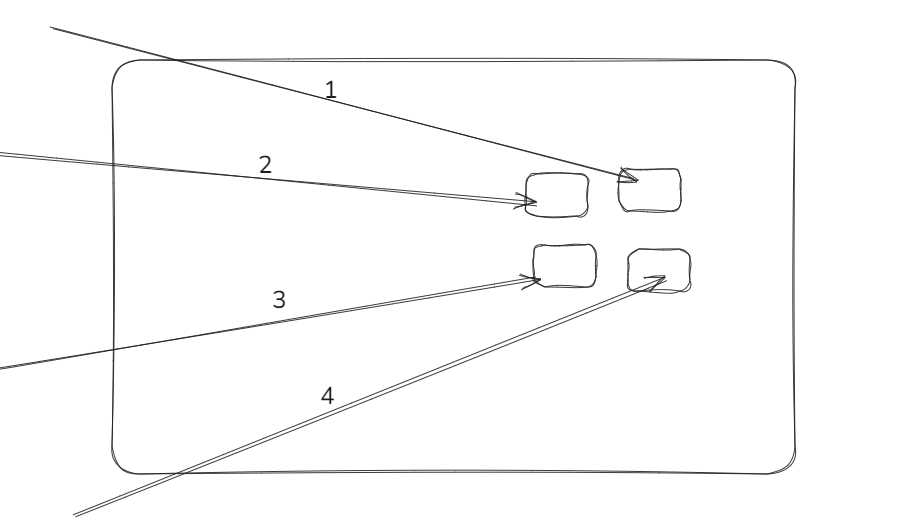

By default, there are 4 threads in the UV thread pool. But what happens if we make 5 file system calls? It means the first 4 requests will block the 4 threads. Each thread will transfer its task to the OS, and once that task is handled, the thread becomes available again to take on the next request. The 5th request will wait until one of the threads is free and available in the UV thread pool.

DNS lookups / Crypto (why they use the pool)

Suppose a request comes for a DNS lookup. A DNS lookup is a heavy task, so it blocks one of the threads in the thread pool. If you request a cryptography task, it also uses the thread pool. Additionally, if anything else comes up that requires C++ code execution, it will also block one of the threads in the pool.

Is NodeJs single-threaded?

Come on! If you say NodeJs is single-threaded, I’ll have to laugh, haha! NodeJs can handle both asynchronous and synchronous code. While it runs JavaScript on a single main thread, it can use multiple threads for other tasks through libuv. So, it depends on what you're doing. You can't define NodeJs simply as single or multi-threaded—it’s more flexible than that!

Code Demo of Thread Pool

If you run the code below, it will take some time but the output will appear at the same time because it uses 2 out of the 4 available threads in the thread pool, and everything runs in parallel. The same thing will happen when you use all 4 threads.

const fs= require('fs')

const crypto= require('crypto')

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("1: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("2: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

//OUTPUT

1: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

2: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

What happens with 5 crypto calls

If you make 5 cryptography calls, one request will be delayed because there are only 4 threads in the pool. The first 4 tasks will run on the available threads, and the 5th one will have to wait until a thread is free. The order of execution is not guaranteed, as the tasks finish based on when threads become available, and that depends on the complexity of each task.

const fs= require('fs')

const crypto= require('crypto')

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("1: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("2: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("3: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("4: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

crypto.pbkdf2('password', 'salt', 5000000, 50, "sha512", function(err, key){

console.log("5: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE");

} )

//output

2: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

4: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

3: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

1: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

5: CRYPTO PRIVATE KEY DONE

Can we change the thread pool size?

The answer is YES! You can change the thread pool size by setting the UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE at the top of your file like this:

process.env.UV_THREADPOOL_SIZE=2

Networking in NodeJs (not the thread pool)

If a user sends an API request to your server, does that API request use the thread pool? The answer is no. API requests use sockets. For each incoming connection or API request, a new socket is created, not a thread. Unlike the "thread per connection" model, where each connection would require a new thread, NodeJs uses a more efficient model.

Instead of creating a new thread for each request, NodeJs uses scalable I/O event notification mechanisms like epoll (Linux) or kqueue (MacOS) to handle multiple requests at the same time without the need for hundreds of threads. This is what makes NodeJs very efficient in handling high numbers of API requests.

Scalable I/O event notification (epoll/kqueue)

epoll (for Linux) and kqueue (for MacOS) are algorithms that handle multiple connections efficiently. When multiple connections are made, epoll keeps track of all of them. If there is any activity, like data to read or write on a connection, epoll will notify libuv. Libuv then triggers the appropriate callback, and V8 runs the callback.

This mechanism is scalable and efficient because it doesn’t create a new thread for every connection. Instead, epoll manages all the connections using file descriptors. This is what makes NodeJs capable of handling a large number of requests without using too many system resources.

This is more on the academic side, related to operating systems, so it can take some time to fully understand. You can read more about it here and here.

Learnings We Got Here

- Never block the main thread (V8's main thread).

- Avoid using synchronous methods on the main thread.

- Be cautious with complex calculations, like regex operations.

- Don't do heavy JSON operations on the main thread.

- Data structures are important because the core of libuv and other systems relies on them to manage tasks efficiently.

- A min-heap algorithm is used by timers in the queue.

- Naming is very important. Clear, descriptive names help make the code easier to understand.

And that's all for this episode!

I'm Rahul Aher, and I'm writing digital notes on NodeJs. If you enjoy these notes, please share them with your friends. If you find any errors or have improvements, feel free to contribute by forking the repo. If you're interested in writing the next episode's notes, fork the repo and contribute. Let's learn together! Also, please consider giving a star to this repo. For any queries, let's connect here.

Thank you so much for reading. If you found it valuable, consider subscribing for more such content every week. If you have any questions or suggestions, please email me your comments or feel free to improve it.

Written by Rahul Aher

I'm Rahul, Sr. Software Engineer (SDE II) and passionate content creator. Sharing my expertise in software development to assist learners.

More about me